Is There a Dunbar's Number for Crypto Communities?

(or... Why Community Infrastructure Matters)

Communities are one of the major backbones of web3.

We’re starting to see this really take full effect: Twitter communities, Discord channels, and niche subreddits dedicated to web3 topics are often some of the best places to learn about new developments in the space, ask questions, and even find friends. Notably, these are web3 communities built on web2 platforms.

But we’re also starting to see more native web3 communities emerge. NFTs are a great example: when a person buys an NFT from part of a collection, they join a community of other owners. Sure, they can make the picture their Twitter profile picture and that’s part of web2, but the community’s roots are tied to verification/authentication properties in web3. Furthermore, these communities are actually often fairly delineated, given that many collections are capped at a certain number of items. Bored Ape Yacht Club, for instance, is an NFT collection of 10,000 digital Apes, and owning an Ape gains one membership to the “club.” BAYC’s Opensea cover photo quite literally looks like a digital clubhouse:

And the creators of Bored Apes are planning on building out an in-person clubhouse, too (if you look closely, you can see “Miami Clubhouse IRL” in the top right):

But is there a standard — or even ideal — size for crypto communities? Is a big community always desirable? Even if the answer is yes, is there a point at which “big” becomes too big? For instance, if Bored Ape builds an in-person clubhouse for everyone that owns an Ape, will it be a club or a concert? (10,000 people is a lot of people). And on the flip side, what’s the downside of having too small of a community?

So far, there’s no standard size for cryto communities. Many of the most notable NFT collections have 10,000 items (think: Bored Ape Yacht Club or CryptoPunks). The Axie Infinity Discord server has 800,000 members (the maximum allowed by Discord), but the typical server only has 10-15 members. Friends With Benefits, a crypto-based social club which has been likened to a “crypto Soho House,” has ~1300 members. Notably, membership requires purchasing 75 $FWB tokens (currently equivalent to ~$7800), so financial barriers constrain access.

Despite this variability, it’s still very unclear if one size is better than another. Both large and small communities have advantages. For instance, a larger community could potentially generate more ideas, expand accessibility, and promote diversity — but it might come at the risk of diluting participation, less passionate members, and spam. On the other hand, keeping a community small and close-knit can facilitate high-quality contributions. But maintaining that small size can be difficult: it often requires sacrificing growth, a financial barrier to entry, or both.

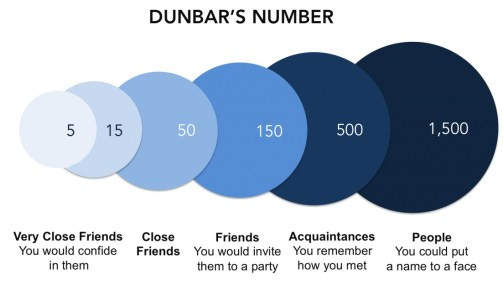

Given these difficulties, I’ve been trying to think about crypto communities from the perspective of Dunbar’s number. Dunbar’s number suggests that there’s a cognitive limit to the number of people one can maintain stable relationships with. The Dunbar framework is broken out into varying levels of relationships, from incredibly intimate to general acquaintance. The number of people within each category grows as the relationship weakens:

The notion of a Dunbar-esque number for communities, however, is a bit tricky. The framework is based off of an individual’s relationships, in large part because it’s easy to draw a line between two people and assess the level of their relationship. That’s not the case in communities. For instance, you could have members A and B fall into the “very close friends category” while B and C might only be “friends.” The question then becomes about the numerous different relationships within a community — e.g., does everyone need to be at least “friends,” or can some simply be “acquaintances?” Furthermore, is there an equilibrium that balances close connections with the ability to constantly meet new and engaging people?

I would imagine a strong community has an average relationship at the actual Dunbar number (150), where you’re “close friends” with some members, “acquaintances” with others, and simply “friends” with most. The problem is, no one knows if 100 or 150 or 200 is actually the right number. Dunbar’s framework is a theory, not fact. And what Dunbar’s number is really getting at is not how many people you know, but the number of high-quality relationships you can realistically have.

Communities can find their Dunbar’s number by setting guidelines for earning membership. Notice I said earning, not paying — someone’s finances are almost never indicative of whether they’ll be a high-quality member of the community. Instead, time-based barriers/challenges are often much stronger way of aligning membership with community goals.

By time-based barriers, I mean that there needs to be some investment of time to gain access. Mason Nystrom, an analyst at Messari, actually wrote about a similar concept with regard to Runescape and NFTs:

Time is universal and naturally limited, making it the most equitable resource — everyone has the same 24 hours. NFTs can take a page from the Runescape playbook by integrating time or labor-intensive tasks into how they are earned.

Communities should take a page from Runescape, too. Task/time-based entry into a community helps ensure the members are constantly contributing. It’s skin in the game - but instead of finances (as is often the case for DAOs), that investment is one’s time.

Mirror, a decentralized publishing platform, kind of already does this — writers can submit articles as part of a weekly “Write Race,” and community members vote on which articles they like best. The ten writers with the most votes each week gain the ability to publish on the Mirror platform and join the community. In this case, the act of the writing an article is the time-based investment — writing takes time, especially if it takes multiple attempts to win the Write Race (which it often can). As a result, the average contribution of each community member is quite high. Currently there are ~250 publishers on Mirror and, based on Twitter interactions, it seems as though the majority of the publishers tend to be quite familiar with each other.

So is 250 the magic Dunbar’s number for communities? Probably not. Again, I think the point is less about setting a target number of members and more about structuring membership in a way that faciliates high quality contributions.

I’m a big believer in the notion that infrastructure design structures incentives. In this case, a core part of a community’s infrastructure is the on-ramp to membership. And while changing existing infrastructure can be quite difficult, that so many of these communities are new and evolving presents an exciting opportunity to design membership requirements in a way that aligns individual incentives with the goals of the community. What concerns me most with the communities emerging today, though, is that many of them seem to evaluate membership (at least in part) on the basis of financial ability — buy an NFT, contribute money to a DAO treasury, purchase a certain number of tokens, etc. It feels as though these web3 communities are becoming increasingly exclusive because of how expensive it can be to gain access.

With that being said, I encourage anyone building communities in web3 — whether it’s NFT collections, DAOs, gaming groups, or whatever — to think about how the on-ramp to their community contributes to the community’s overall goals. The Dunbar’s number for communities is likely not actually a number, but a range of numbers, determined in large-part by the quality of a community’s underlying infrastructure. And I’ll be the first to admit that there are probably better ways of designing access beyond time-based tasks, but I do think they are better than the financial gateways we’re seeing gain traction today. It’s still so early in the development of web-based, decentralized communities. But once the infrastructure is set, it’s pretty hard to change. So let’s not mess this up.

Thank you to Spencer and Nishita for reading drafts of this post.